Supply-chain finance: a new spin on a prehistoric notion

The Australian financier guiding the now collapsed finance group Greensill Capital pitched his small business as an agent of “technological disruption” that aimed at “democratising capital”. But what Lex Greensill was really offering was a new spin on a form of financing that dates back again at the very least 4,000 several years to Bronze Age Mesopotamia.

The trading of invoices by intermediaries served finance medieval European commerce, the expansion of the British empire and the 20th century US textile industry. Now a modern incarnation — in the variety of offer-chain finance — is attracting a great offer of scrutiny subsequent the failure of Greensill in March.

For generations, monetary middlemen — generally banking institutions — lent dollars to suppliers of goods who did not assume to be paid by their buyers for quite a few weeks, right up until the end goods had been offered on the open up sector.

A merchant, for example, could possibly not be paid out until eventually a tailor who had bought their cotton had manufactured and marketed the finished items of garments. Instead than waiting around to be paid out, the service provider would promote their bill to a bank or other loan provider and acquire a minimal a lot less than the price of the cotton. The middleman would then collect the complete payment from the tailor at a afterwards day.

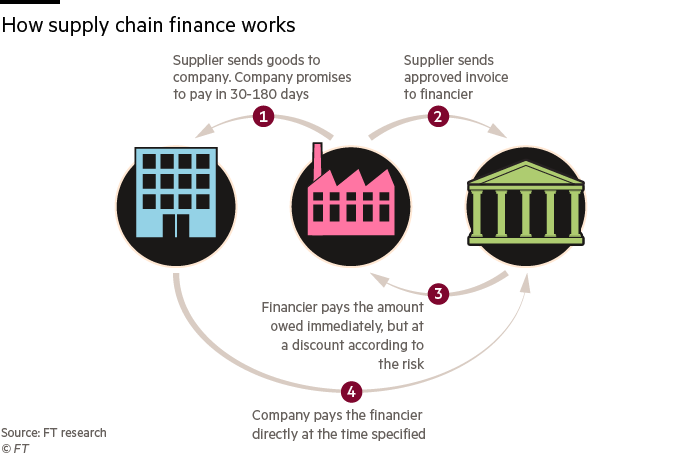

Provide-chain finance, which has grown in popularity in excess of the previous two decades, switches the creditor romantic relationship.

In this design, the customer of goods, for case in point a grocery store, offers its suppliers access to supply-chain finance presented by its financial institution. Somewhat than ready for payment right up until the milk supplied to the grocery store has been bought, a dairy farmer can submit an permitted invoice to the financial institution and get a payment that is far more well timed but a bit considerably less than the complete price of the order. The bank afterwards collects the total quantity from its client, the grocery store.

Simply because the lender is extending credit to the supermarket relatively than the dairy farmer, it assesses the loan on the supermarket’s credit score score, which is possible to be more robust as a substantially bigger small business. The hazard is for that reason perceived to be reduced and the financing more affordable.

Push from the pandemic

In accordance to consultancy Oliver Wyman, up to 80 for every cent of offer-chain funding is carried out by huge banks, with most of it provided to domestic clients. But a rising amount of specialist non-financial institution organizations these kinds of as Greensill are relocating into the industry, and they have better returns in their sights.

Interest in provide-chain finance also amplified previous yr as the pandemic threatened corporations and created their suppliers ever more vulnerable.

“Covid ripped a large amount of field apart and set strains on money flows — so this was an very important tool to retain tiny and medium companies in enterprise,” said Eric Li, head of transaction banking at Coalition, which screens banking tendencies. “Supermarkets weren’t heading to go bankrupt, but the similar couldn’t be mentioned about little dairy farms.”

Most huge financial institutions supply offer-chain finance to their major shoppers, normally blue-chip organizations with financial commitment-grade ratings. For the banking companies themselves, it is a lower-margin enterprise that is considered reasonably risk-free of charge for the reason that default rates are normally reduce than for other styles of lending.

The sector has developed steadily more than the past decade, from $20.6bn of world revenues in 2010 to $26.6bn last yr, according to Coalition. Much more than fifty percent of that was from Europe, the Center East and Africa.

Although offer-chain finance presents some defense to supply chains, another gain for consumers is the prospective to put off when they fork out back the lender. Alternatively than settling just after 30 or 60 times, as they may possibly typically with suppliers, they can press again payments by as a great deal as 180 days. In some instances, compensation conditions have been lengthened to 360 days.

For analysts searching at bank debt stages, this can induce a problem simply because, from an accounting perspective, provide-chain finance is not handled as debt.

“If the financial institution extends the reimbursement day materially, we see it as having a credit history line from your financial institution,” reported Frederic Gits, group credit score officer for corporates at Fitch Ratings. “Disclosure has hardly ever been really fantastic.”

Issues of disclosure

Ranking organizations, regulators and auditors have prolonged complained about the lack of disclosure on source-chain finance debt. In 2019, the Huge Four audit companies wrote a joint letter to the US accounting watchdog FASB inquiring for “greater transparency and consistency”. But minimal has modified so much.

“This lack of advice [from accounting bodies] usually means that people force the boundaries,” Gits mentioned. “It’s feasible to detect, but not generally simple.”

He pointed to substantial-profile company collapses at Carillion, NMC Overall health and Abengoa the place it was only following the corporations defaulted that it was recognized to what extent they had employed supply-chain finance.

But inspite of the collapse of Greensill and the amplified target on this certain financing product, banking companies are unlikely to go out of the market.

“It fulfils a have to have and the banking institutions are all really relaxed with what they are doing,” mentioned Kevin Working day, main executive of HPD Lendscape, a funding know-how supplier. “It’s all run in just fairly harmless parameters and there is lots of working experience in terms of the concentrations of funding to offer and threat diversification.”

Certainly, when Greensill filed for insolvency, many worldwide banks stepped in to supply funding to its former shoppers, which integrated large healthier businesses such as Vodafone and AstraZeneca.

But at the exact time, a number of expert, non-lender teams have grown up and now account for the 20 for every cent of the market place not managed by large banking companies, in accordance to Oliver Wyman.

Like Greensill, they hoped to turn a staid, low-margin business enterprise into a far more rewarding organization, employing AI and other engineering to improve effectiveness.

Greensill struck offers with consumers that bore small resemblance to regular supply-chain funding, presenting significantly lengthier reimbursement terms and advancing money from predicted upcoming receivables.

In contrast to banking companies, which use their harmony sheets to fund supply-chain funding, Greensill also used cash from buyers in items sold by Swiss teams GAM and Credit Suisse.

Working day warned that, as with Greensill, all those making an attempt to disrupt the field have frequently taken on possibility that financial institutions and other additional conventional rivals would be unpleasant with.

Loads of having difficulties corporations are attracted to offer-chain finance due to the fact the accounting disclosure guidelines make it easier to mask this kind of personal debt.

Most of the new entrants offering provide-chain finance are wanting for “quite superior returns,” Day claimed. “But this is not a higher return sector.”

“It’s meant to be lower hazard. If you are anticipating to get superior returns, you will consider significant risk . . . People are employing buildings that are intricate for points that are essentially really very simple.”

Gits stated the demise of Greensill experienced set force on regulators and accounting bodies to tighten rules and transparency specifications for supply-chain financing.

“Greensill was just a compact section of this significantly larger market, but they have turn out to be the poster kid for it,” he mentioned. “A large amount of the new entrants are fewer regulated. They had been pushing the boundary of the strategy to the stage it could be abused.”